From Lightning to Drip Torch: The History and Ecology of Fire

We Didn’t Start the Fire:

Burn Unit 4

Written by: Paxton Caroline Hayes

Photos taken by Paxton Caroline Hayes

Location:

McDuffie PFA in Dearing, GA

History of Fire

Well before humans populated the Southeast, wildfires ignited by lightning strikes created and maintained the landscape. As a result, the most iconic plants and animals of the Southeast co-evolved to thrive with frequent and low intensity fires. These regular, natural disturbances shaped the land into the diverse and fire-loving ecosystems that we know today.

Indigenous populations observed the benefits of fire and learned how to strategically apply it for various purposes, including clearing land for agriculture, hunting, and for resource management. For more than 10,000 years, anthropogenic fires were used as a way to support a healthy ecosystem while mitigating risk to human development. Indigenous peoples’ intentional use of fire, referred to as cultural burning, demonstrates the vital role that fire plays as a land management tool.

With the onset of European colonization, and later the logging industry of the 19th century, fire suppression began throughout North America. With the loss of frequent fire, forest fuels began to build up in fire-evolved ecosystems. This led to an increase in catastrophic wildfires throughout the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s, severely damaging ecosystems and human-developed areas.

In the 20th century, we began to understand the impact of long-term fire suppression. With collaborative efforts between government agencies, non-profit organizations, private companies, and individual advocates, we have started the process of re-introducing fire to the ecosystems that need it. Over time, with the continued use of prescribed fire and other land management efforts, we will begin to see healthier, more resilient ecosystems and decreases in catastrophic wildfires.

Ecology of Fire

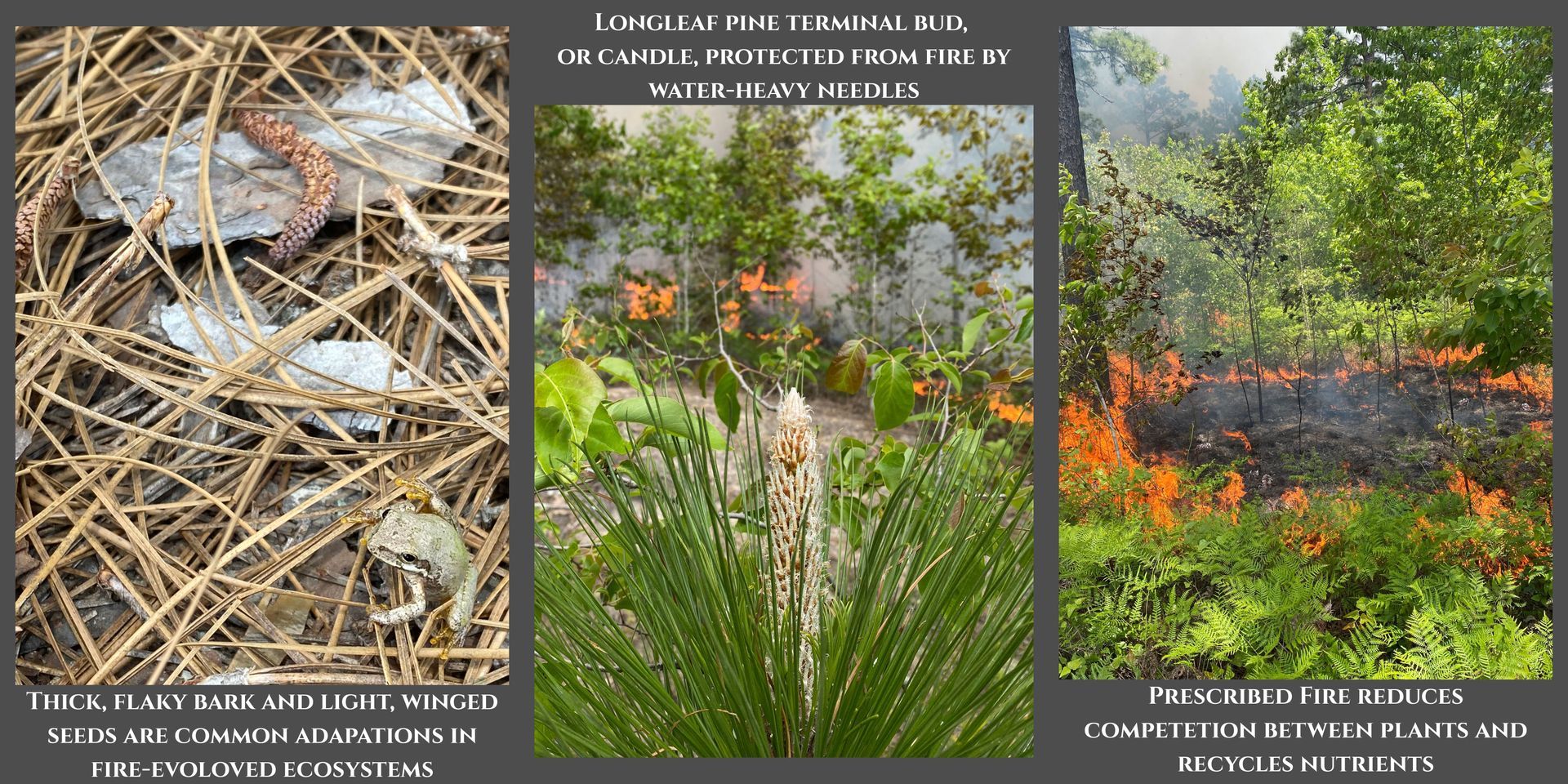

In addition to reducing wildfire fuels, prescribed fire has several positive ecological outcomes. Fire cycles nutrients back into the ecosystem, reduces competition for resources between plants, improves habitat for wildlife, and improves access to natural resources. These benefits encourage strong and diverse ecological communities and more accessible landscapes.

Plants have evolved different adaptations to survive and even thrive with fire. Some trees, like the longleaf pine, developed a thick and flaky bark layer to protect themselves from the flames. Other conifer species developed light or winged seeds to ensure resprouting once the fire has passed. Some herbaceous plants, such as wiregrass, evolved to have meristems that are buried in the ground (like the rhizomes for your mom’s irises), so that the fire does not consume all their nutrients and they can resprout almost immediately.

Ecological communities have also developed shared adaptation. In some ecosystems we see a limited overstory layer with a diverse, fire-adapted understory. Pine savannahs and open woodlands have scattered overstory trees rather than a continuous canopy, limiting the opportunity for fire to become so intense that it causes tree mortality. In other ecosystems, we see a diverse set of overstory trees that can regenerate through basal sprouting. Longleaf pines and oak-dominated hardwoods are often seen in forests that have this community adaptation.

Co-Evolution in Action: The Longleaf Pine

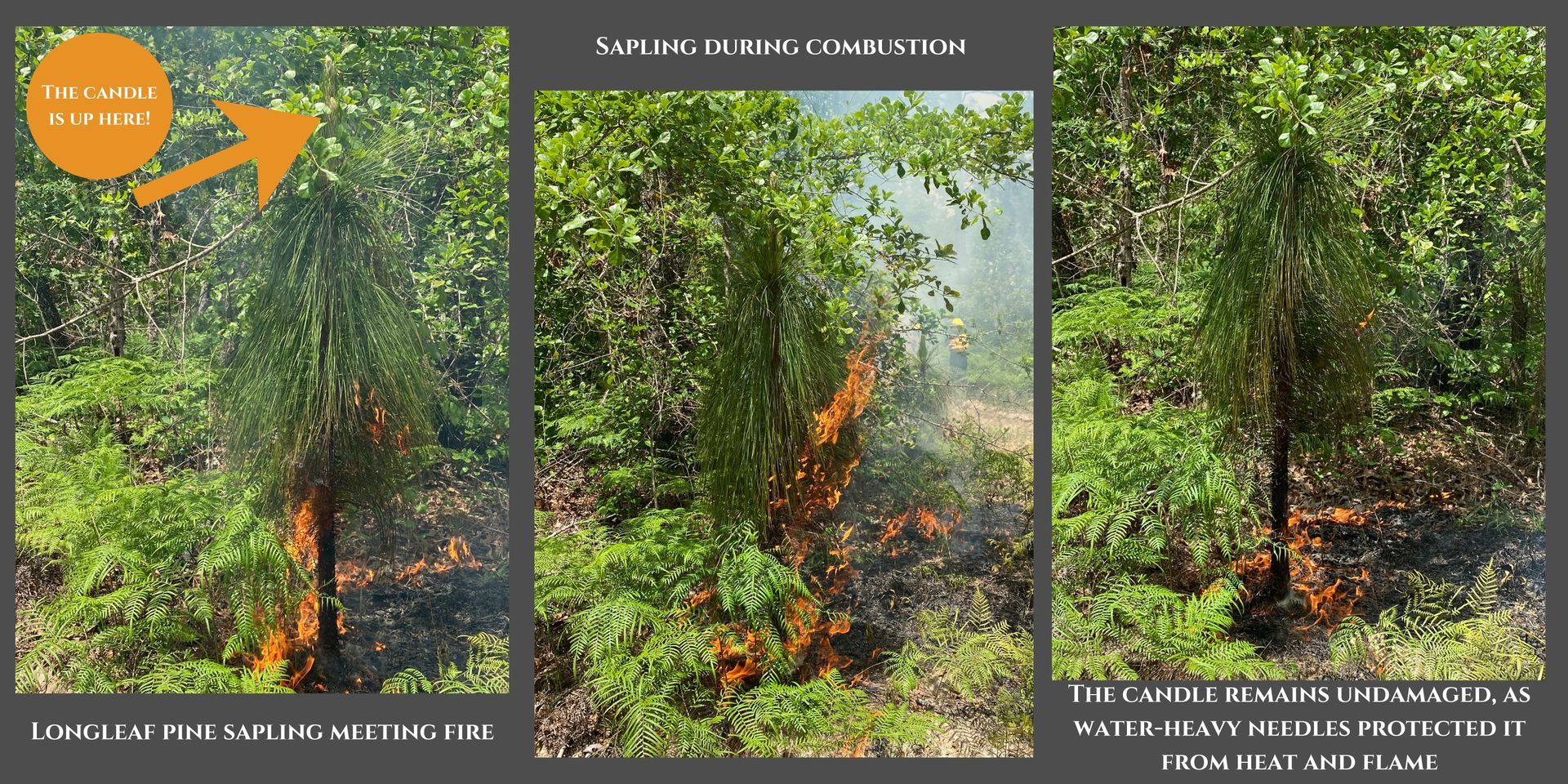

The longleaf pine is one of the most widely-known trees in the Southeast. These trees have co-evolved so that fire is necessary for a healthy pine forest. In their seedling stage - often called the “grass stage” because they look like tufts of grass - longleaf pines are extremely fire resistant. The seedling shoots out water heavy pine needles in all directions, ensuring that it is protected from heat and flames. Once fully mature, the longleaf pine is a tall tree with branches well above flame height, serotinous pinecones that only open to release their seeds after reaching a certain temperature, and thick, flaky bark to protect the trunk of the tree.

But when the longleaf pine is in its growth stage—when a terminal bud, or candle, is present—it is highly susceptible to fire damage. In order to survive, longleaf pine saplings grow as tall as possible in a single year while the candle grows straight up toward the sky. The candle is also surrounded by a cluster of water-heavy pine needles that are harder to burn. By growing in this way, the candle is insulated from the heat and flames of low-intensity fire.

Press & Media Inquiries

Contact Us

About Southern Conservation Trust

At Southern Conservation Trust, we are passionate about elevating nature through exceptional stewardship. Based in Georgia, our 501(c)(3) public charity has successfully conserved over 65,000 acres of land across the Southeast, including five public nature areas in Fayette County and the Fayette Environmental Education Center. We believe that protecting our natural spaces is just the beginning; everyone should have equal access to enjoy the beauty of the outdoors. Join us in our mission to foster a deeper connection between people and nature. Learn more at www.sctlandtrust.org.